Sometimes we give up.

Sometimes on SAR missions we return day after day, then week after week, without finding our lost person. The search is called off. Volunteers leave the scene in quiet resignation. Families leave the scene in despair.

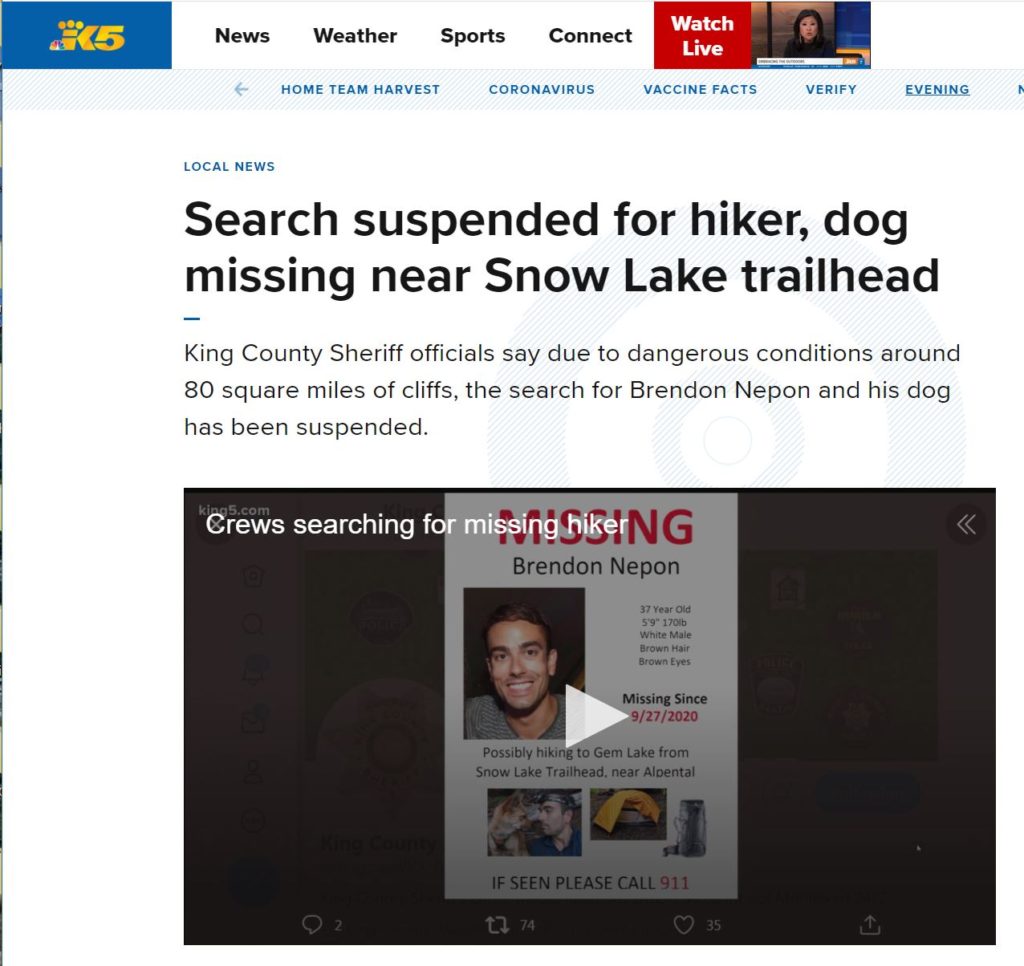

In the last six months here in the Pacific Northwest, we’d had at least four such protracted, and ultimately barren, wilderness searches. SAR volunteers returned again and again to hike miles up into the mountains to reach their search areas. Helicopter searches were conducted when weather permitted. Drones were used to search otherwise inaccessible slopes and ravines. Specially-trained K9 teams were deployed in attempts to locate either signs of the living or scent of the dead. All to no avail.

When a search goes on for days with no trace of the subject found, the planning team starts to get concerned, as they’re faced with two difficult questions:

Is the missing person in our search area – and just extremely hard to find? (A common occurrence here in the rough mountains of the Pacific Northwest).

Or . . .

Has our subject managed to travel outside the boundaries of where we are looking? (Which sometimes happens if a person gets onto the wrong trail system, or travels long distances along a linear feature, such as a river drainage).

Do we take our limited volunteer resources and look harder or should we direct our searchers to look wider? Sometimes we just don’t have enough information to guide that decision.

Each operational period (typically a 12-hour search day) begins with hope: Today’s the day we’ll find our subject. Today’s the day we’ll find a clue. Today’s the day my K9 will catch the scent of our missing person. Today’s the day.

Each operational period ends with tired and determined volunteers returning to search base, speculating on why we haven’t found our missing person, and . . . more often than not, willing to return to search the very next day.

Until something happens that we never want to happen. The search is suspended.

Suspending a search is something a search manager never wants to have to do, and in well-run searches is a decision reached via a formal evaluation of the following questions*.

- What are the odds that our missing person is still alive?

To answer this question, search managers must consider how well the person was prepared for the conditions they may face. Day hikers typically carry minimal extra survival gear, clothing, or food, as opposed to backpackers who are much better prepared for unexpected nights out. We also need to consider if our subject had pre-existing medical liabilities, if the subject had any survival training or experience, and if there are terrain hazards in the search area.

What is the impact of weather on survivability?

We need to consider if the weather has been cold or enough to induce hypothermia, which is the most serious risk our lost subjects will face. Bad weather has the dual effect of reducing the survival time of lost subjects and limiting the ability of searchers to find them.

Is it safe to continue to send searchers out?

Bad weather, searcher fatigue, and dangerous terrain are the largest threats to searcher safety. In a recent mission, we were faced with the choice of sending tired searchers to ford a dangerous river crossing or directing them to hike miles just to reach a high alpine search area that was threatened by storms on an almost daily basis.

Have all planned search objectives been met?

Have we searched in all planned areas, and have those areas been searched thoroughly enough? The first part of this question is usually easy to answer, returning teams report where they have searched, and we can examine the electronic tracks captured by their GPS units.

Answering the second part of this question is a much harder proposition, can involve huge amounts of uncertainty. If we’re grid-searching a uniform field, we can, with some effort apply principles search theory to estimate how much “probability” has been searched out of each area. When uniform fields are replaced by mountain slopes, crenelated with ravines and ridges and covered by snowfields or dense forest, our ability to answer the question: “Have we searched enough?” leaves us second-guessing our second guesses. (See Your Worst Nightmare and Probability of Detection).

And when these hard questions have been answered as best as we can, sometimes the right answer is “stop.” Stop the mission; stop putting volunteers at risk; stop burning through SAR resources with limited chance of success.

And so, we give up; move on; and rest up for the next mission.

A missing person’s family seldom agrees. Families understandably would never call off a search. And for that reason, we soften the language and refer to “scaled back efforts,” “active monitoring,” or “continuous limited searching.” But in the end, all of this language means we’ve stopped sending search teams out day after day.

It’s what we never want to happen. It’s something we face every year.

*Source: The Textbook for Managing Land Search Operations, R.C. Stoffel, ERI Publications. (https://www.amazon.com/Textbook-Managing-Land-Search-Operations/dp/B004FD1UKW/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=The+textbook+for+managing+land+search+operations+Stoffel&qid=1611010793&sr=8-1)

0 Comments